Distributed cognition refers to the way that individuals think and learn with technology. Salomon and Perkins (2005) identify numerous different types of technology: the traditional sense of technology today (i.e. computers, phones), technical tools (i.e. pens, pencils, paper), symbol systems (i.e. language, music), and the sciences and their notations (72-73). I will use this broad definition of technology throughout this paper. The theory of distributed cognition rejects the idea that human intelligence is isolated in the individual. Instead, it explores how intelligence is developed across multiple systems, both the human and technological, which work together to allow people to carry out cognitive functions.

Furthermore, Morgan et al. (2008) explains that distributed cognition focuses on “how people can be enabled by the environment to undertake highly complex tasks that would usually be beyond the abilities of the unassisted individual” (127). Morgan et al. highlights the power of technology in showing that, not only does technology work with the human mind to carry out cognitive functions, but it also helps people to complete cognitive tasks that they could not complete otherwise. Distributed cognition dispels the common misconception that technology is a cognitive crutch for people. Instead, the theory of distributed cognition invites an understanding of thinking and learning as a cooperative process between people and technology.

The Lesson

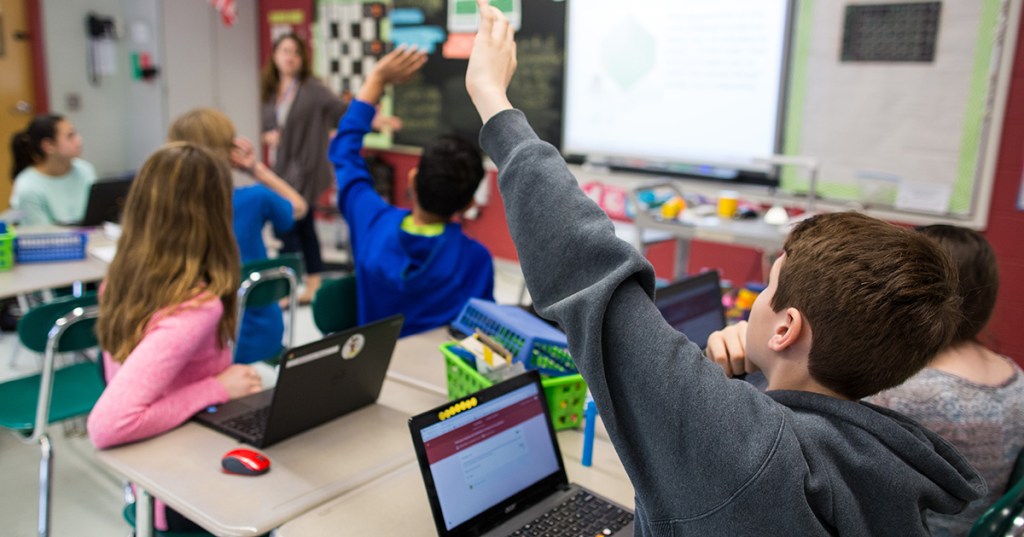

The idea of distributed cognition is seen in many ways in Ms. McAllister’s 6th grade ELA poetry workstations lesson. First, Ms. McAllister uses (what looks like) an iPad to project her Prezi onto a Smartboard to give a brief lecture about poetry and analyze a few poems with the students. The presentation is interactive because students use “ActivExpressions,” a type of clicker, to answer questions and offer their ideas and opinions. The most extensive uses of technology integration is through the three poetry workstations: iPod, Techie, and Podcasting. These three stations are driven by the same series of reflection questions about poetry.

At the iPod station, students watch “poetry in motion” videos, which bring poetry alive through digital stories. After watching these videos, the students respond to discussion questions by writing on post-it notes. At the techie station, students use laptops to blog about their chosen poems; they write about the author’s purpose, theme, feelings/mood, etc. In addition to creating their own posts, students comment on their peers’ blogs, which is similar to our ED 386 class. Lastly, at the Podcasting station, students have the option to create a radio show, interview, video podcast, or audio podcast based on a previous project about poets. To complete these projects, they used laptops, headsets, and what seemed like a specific type of software for podcasting, but the teacher does not specify. The students were extremely creative with these projects. For example, some students took on the identity of their poet while others did a commentary on the person’s poetry.

Effects with and Effects of

Ms. McAllister’s diverse integration of technology exemplifies many different components of distributed cognition, such as Salomon’s and Perkins’ (2005) concept of the effects with and the effects of technology. They define the effects with technology as how technology enhances intellectual performances (72). In this case, once the technology is removed, the person’s cognitive competence decreases. For example, the teacher’s use of a Prezi demonstrates an effect with technology. The Prezi increases the teacher’s capacity to present the information in an organized and engaging manner, which may be lessened if the teacher used a traditional, technology-free lecture. The ActivExpression clickers afford the students a similar amplified performance by allowing everyone to contribute to the class discussion. For example, without the use of these clickers, more introverted students may be fearful to participate; however, with the clickers, they can contribute in more meaningful ways by answering multiple choice questions or submitting written answers, enabling these students to demonstrate their academic abilities.

The use of the iPods to watch digital stories of poetry is also an effect with technology. By hearing the poem read aloud and seeing corresponding images, students develop a more thorough, holistic understanding of the poem that if they were to read it on paper. The students can better analyze the poems when they understand them in different dimensions and forms of media. For example, hearing the poem out loud could allow students to more clearly hear the poem’s onomatopoeia. Similarly, seeing the images may make students more aware of imagery.

The digital stories on the iPods augment students’ ability to analyze the poetry, which can also be an effect of technology. Salomon and Perkins (2005) describe effects of technology as when the use of the technology leaves long-lasting effects on the individual, either augmenting (or diminishing) cognitive functions, even after the technology is removed (77). Students can retain the cognitive abilities they learned through watching the digital stories to analyze poems on their own. In other words, as an effect of watching these videos, students will be more aware of the visual and auditory aspects of poetry even when they are just reading poetry on the page. The use of the videos on the iPods is an example of how “supportive technology—the notations, the rules, the training wheels—is designed for temporary effects with leading to lasting effects of” (79). These videos first act as scaffolds for the students, in unlocking different aspects of the poems that they could not see otherwise. However, the students can then understand and analyze the poems on their own, transitioning from effect with to effect of.

The techie station, which involves blogging, is also an example of the effects of technology. Blogging and commenting on other people’s posts affords students the skills of digital etiquette. Through these activities, students learn how to write for virtual audiences in an appropriate way. For example, when commenting on other people’s blogs, students learn to be respectful and tactful, especially when disagreeing with someone’s argument. The cognitive function of having digital discussions is transferable across any digital platform, such as peer reviewing, Google docs activities, emailing, texting, etc. Blogging also affords design skills, such as creating a balanced layout between words and images. Even after students finish their blogs, they can still apply their newfound awareness of spatiality and aesthetics to other situations. Blogging allows students to develop cognitive skills that last long after students stop using the technology.

Translation

Martin (2012) creates the CTOM framework (connection, translation, off-loading, and monitoring) that applies the principles of distributed cognition to pedagogical methods, which emphasizes that student learning requires two or more cognitive systems. Translation is when technology transfers information from one representation to another. Ms. McAllister’s use of the three stations is an example of translation in itself. Each station is guided by the same concepts and reflection questions, but the information takes on different forms: visual at the iPod station, written at the techie station, and auditory at the podcasting station. Although the students are dealing with similar concepts at each station, the representation is different, which “makes information available that was previously unusable” (Martin, 2012, p. 93). These various representations allow students to understand the information in different capacities and to develop various cognitive functions, such as critical thinking, making inferences, analyzing, role playing, etc.

The iPod station is also an example of translation, as the digital stories transform written poems into a visual and auditory sphere. However, since I already discussed the iPod station extensively, I will focus on the podcast station. This station adds another layer of translation, as students are translating their previously-completed poet projects into this new auditory format. While the teacher never explicitly describes the poet project, I assume that the students had to write an essay, make a PowerPoint, or develop a graphic of some sort, which they are then transforming into a radio show, interview, or podcast. By translating the visual to the auditory, students are developing their speaking and listening skills while also making decisions about what to pull from their original project that will be effective in this new format, which requires an immense amount of critical thinking and application.

Off-loading

Technology is often used for off-loading, which is meant to increase efficiency by allowing the technology “to perform tasks that are tedious, difficult, error-prone, or time-consuming” (Martin, 2012, p. 93). When individuals off-load these tasks, they can focus on more complex cognitive functions. Ms. McAllister implements off-loading by using laptops, specifically at the techie station for blogging. While this function of laptops is not highlighted in the video, I assume that students are using spell check and autocorrect to write their blog posts, allowing them to focus on the content of their writing rather than the mechanics. The use of off-loading in this way makes sense, as a command of English language conventions was not one of Ms. McAllister’s learning objectives for this lesson. In addition, the use of blogging off-loads the possible responsibilities and complications with communicating online because the students can easily just comment on each other’s posts. Rather than worrying about emailing or coordinating times to meet in-person, students can focus on responding to their peers’ ideas, as the blogging software facilitates the communication function. Lastly, and most simply, the students probably saved their blogs to a word processor, which is a basic form of off-loading, as explained in Salomon and Perkins (2005).

Another way that Ms. McAllister off-loads is by allowing her students to keep a list of the reflection questions from station to station. These discussion questions give the students guidance regarding the poems. Rather than struggling to analyze the poems independently, the students have prompts to scaffold their thinking, which may be especially helpful for students who are confused about the concepts. In addition, the students are allowed to keep these questions; they do not have to worry about memorizing the learning objectives because they can always consult the worksheet.

Monitoring

Martin (2012) also describes the principle of monitoring, which refers to assessing the quality of coordination between cognitive systems, such as the human and the artificial. In the classroom, monitoring takes place through formative assessments, which are used as check-ins of student understanding to guide the teacher’s instruction. Based on these formative assessments, teachers can also give feedback to the students on how to improve. Ms. McAllister’s lesson plan has numerous ongoing opportunities for formative assessment through technology. First, the “ActivExpression” clickers offer immediate feedback about her students’ level of understanding during her lecture. From the results of these clickers, Ms. McAllister can adjust her instruction to support students when they do not understand the information or move onto the next concept when they do.

Each station also uses technology to monitor student progress. The post-it notes from the iPod station allow the teacher to assess how the students are analyzing the different dimensions of poetry. The students’ blog posts at the techie station show how they are thinking through the ideas independently, and the comments illustrate how students are refuting or expanding on their classmates’ ideas. As discussed with off-loading, spell check and autocorrect can offer immediate feedback to the students about their spelling and grammar. I do not know if the podcast station tasks are summative or formative assessments. Whether the assessment is based on the final product or on the teacher’s observations through the process, the podcast assignment assesses students’ ability to make inferences about their poet in addition to their speaking and listening skills.

To support the students, the teacher acts as a third party between the students and the technology by offering feedback about the student’s progress and performance at each station. In the video, Ms. McAllister offers informal feedback verbally, as she observes her students working at the various stations. In addition, I assume that she will offer feedback on the final products from each station, which will not only address the students’ understanding of the information but also their ability to work with the technology.

Does technology make us smarter?

After analyzing the video, I would argue that the technology Ms. McAllister integrated into her lesson made the students smarter. Through Salomon’s and Perkins’ (2005) idea of the effects of technology, the students could have gained concrete cognitive functions, such as the ability to analyze poetic devices and to maintain digital conversations. Even after the students stop using the technology, these cognitive skills have the potential to remain. Despite these cognitive skills, the technology most likely did not raise these students’ GPAs; however, Salomon and Perkins encourage us to break away from the “essentialist conception of being smart as if nothing counts as smarter but the bare brain functioning better.” They continue, “The success of human beings in this world plainly does not depend on bare brains any more than it depends on bare hands” (75). Salomon and Perkins highlight that the prevailing definition of smart is a narrow one, which the theory of distributed cognition refutes.

Evaluating intelligence based on the isolated function of the brain is unrealistic, as people are almost always using some form of technology to think and learn with, from language to a pencil to a computer. Therefore, we must look beyond the bare brain to the students’ cognitive performances, which were undoubtedly enhanced, or made smarter, by technology (Salomon & Perkins, 2005). Through the various types of technology that Ms. McAllister used, students were able to analyze the many dimensions of poetry by watching digital stories, to have in-depth discussions with their peers by blogging, and to step into the shoes of a poet by podcasting. As evidenced by these performances, the integration of technology has undoubtedly made these students smarter by supporting and challenging their cognitive development.

You must be logged in to post a comment.