Distractions

After spending more time playing this game, I have noticed a few downfalls. For example, there are many distractions from the central purpose of the game, such as an arcade, pet store, clothes shop, etc. These extra pieces are completely unrelated to the game’s various islands and missions, and they may draw students’ attention away from the richer parts of the game. Therefore, one possible role of the teacher is ensuring that students are engaging with the more mission-based, narrative aspects of the game.

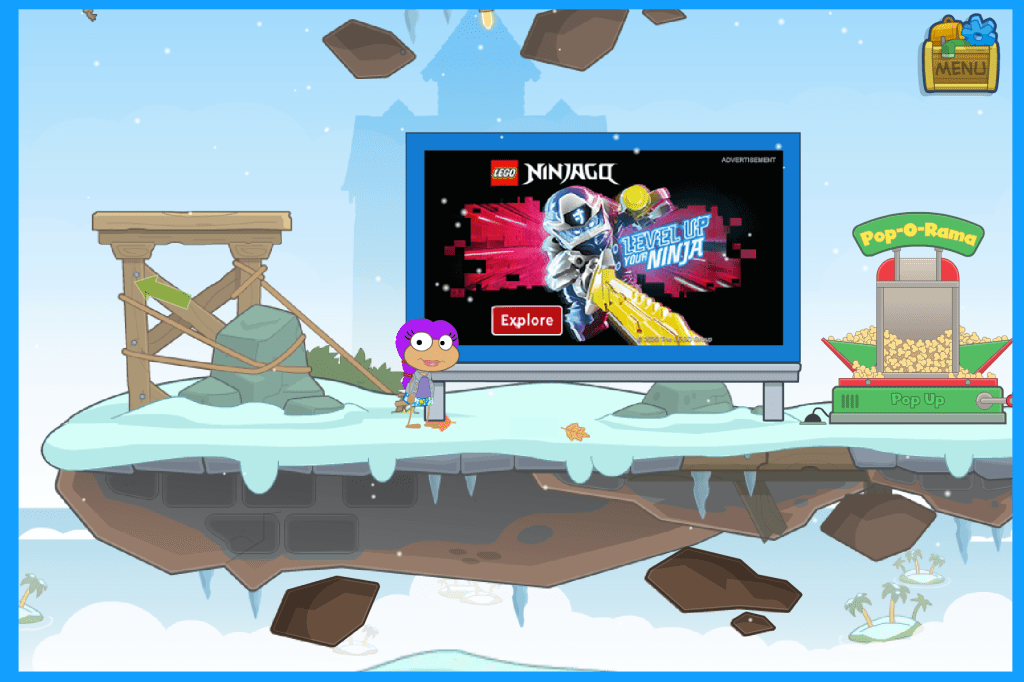

Advertisements

The free version of the game is full of advertisements. In many cases, students must avoid enticing click bait to pass from one setting to another, even within one island. While this is a potential downfall, these advertisements may also provide important teachable moments. Students must learn to exercise self-control and discipline while browsing the internet, and they can practice and develop these skills in the low-stakes environment of classroom game play.

Too “Game-like”?

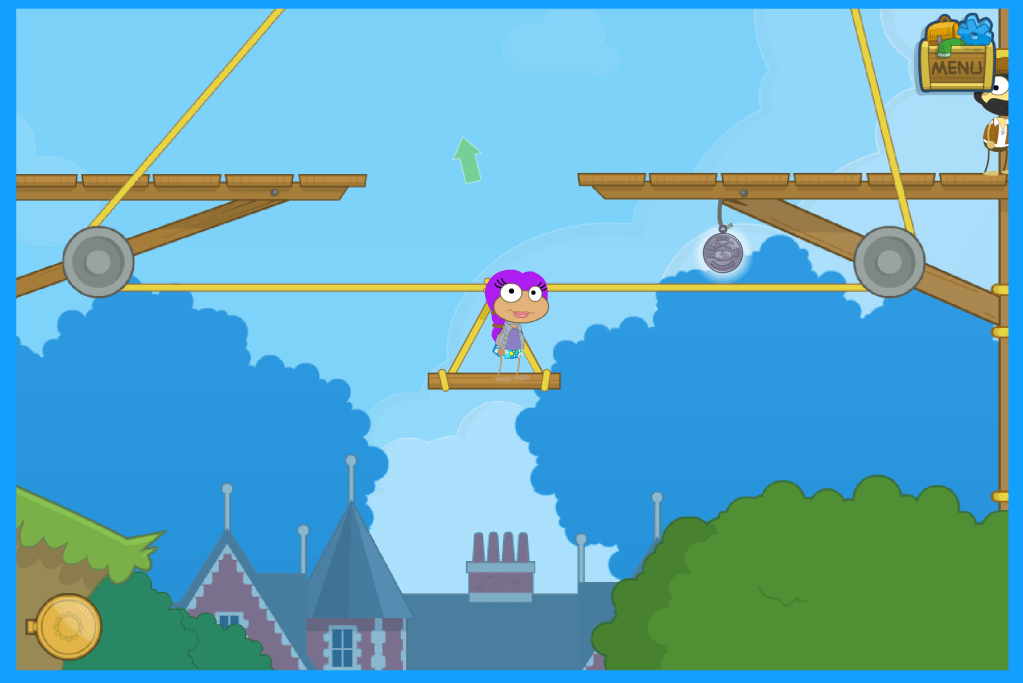

Similar to the unrelated components of the game (i.e. pet store, arcade, etc.), I have discovered that some missions within the islands do not possess much educational value. Returning to “Time Tangled” island, one aspect of the mission is jumping to grab a medal in a difficult position. I tried multiple times before successfully obtaining the medal, and I grew frustrated with this aspect of the game. It was troublesome that, without acquiring the medal, I could not even complete the next objective. I was stuck. This mindless mission detracted from the game’s overall exploratory, creative nature. As a result, I fear that students would become too caught up in aspects of the game that involve mouse dexterity rather than focusing on the valuable overarching mission, which is an inherent problem with the mechanics of the game.

Another aspect of the game that may detract from its creative, exploratory nature is the ability for players to bypass the more content-driven, skills-based aspects of the game once they understand the strategies needed to pass the island. For example, while the “Time Tangled” island is confusing at first, there is a clear pattern to the mission, which I discovered after playing for awhile: once you return an object to one time period, you gain information about the next step in the mission.

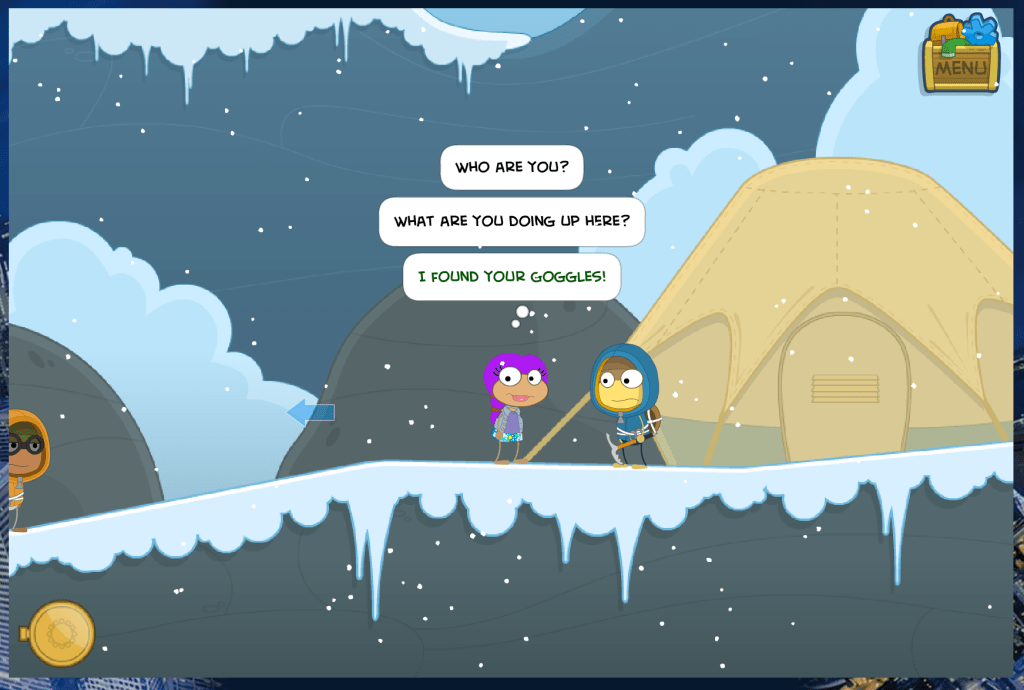

Furthermore, there were times when I found a missing object before talking to the people I was “supposed to talk to” first. As seen below, I found Edmund Hillary’s goggles before getting the chance to talk to him to figure out what he needed. Therefore, I could skip the “Who are you?” and “What are you doing here?” questions and simply give the character the missing object to move forward in the mission. However, if I was a student playing, I would miss out on the opportunity to find out who this character was and what he did — Edmund Hillary, the first man to climb Mount Everest.

This downfall of the game reflects one of Squire’s concerns about video games as ‘designed experiences’: “A number of educators and critics have raised valid concerns that what players learn from games is not the properties of complex systems but simple heuristics (e.g., one learns the strategic necessity of always keeping two spearmen in every city). The fear is that without access to the underlying model, students will fail to recognize simulation bias or the ‘hidden curriculum’ of what is left out” (Squire 2006, p. 21).

After playing for awhile, I could easily figure out the strategy of the island. Therefore, I could just go through the motions without taking advantage of the skills and content knowledge that the game afforded, as explained by Squire in the above quote. I knew that I needed to give the character the goggles, so I bypassed the more substantial aspects of the game in order to complete the island faster.

I think students might become too wrapped up in the heuristics of the game without acknowledging its underlying model. Unlike the McDonald’s game that we played in class, Poptropica is not directly trying to convey a specific ideological message; however, there are definitely important messages within the game that students could miss if they are not paying close attention. For example, the “Time Tangled” island affords the possibility of multiple understandings of history by incorporating various cultures and time periods throughout the game. However, students could easily overlook this aspect of the game if they become too engrossed by completing the various missions; this is where the teacher comes in. I believe that Poptropica can still be an effective game if teachers provide the students with guidance, especially by pointing out the games’ intricacies and connecting them back to the overarching lesson.